A Quick Overview of QUIC and HTTP/3

A congenial guide to the upcoming revolution of the web

It’s quite evident how much we are dependent on the web. While some of us brag about being web developers, others are still intimidated by the information the web overflows us with. Ever wondered how the web works behind the scenes?

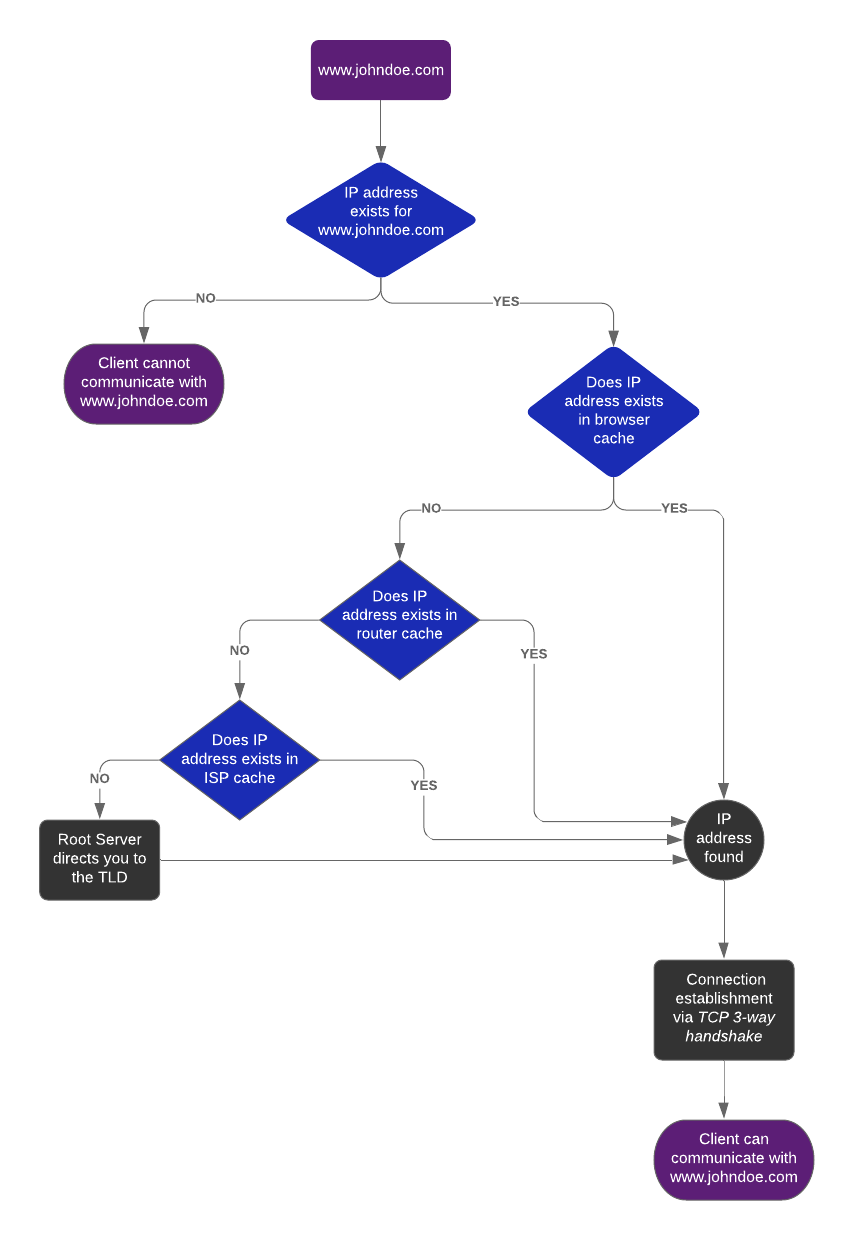

What really happens when you hit www.johndoe.com?

I’ll try to keep it as simple as possible, so here it goes— every domain name is associated with an IP address that the web understands. When you enter www.johndoe.com, it initially looks up for its IP address in the browser cache. If it is not found in browser cache, it looks up for it in the router cache and ISP cache.

If the above steps don’t return the IP address, it is then requested to the root server which tells you from where you can get the information, i.e top level domain (TLD). The TLD let’s you know the IP address of your domain name (search input) and then you can initiate a connection with the domain.

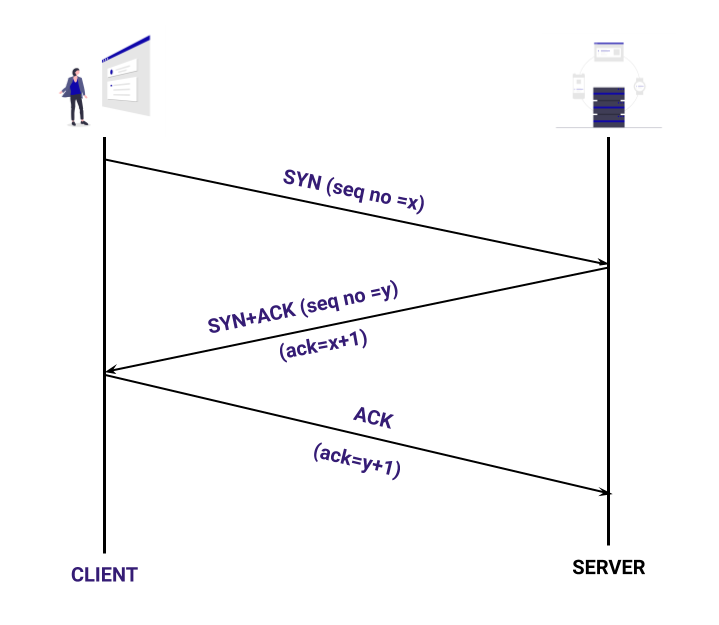

The connection is established in three steps and is known as TCP 3-way handshake. After successfully connecting with the server, you can then communicate with the domain and send requests according to your needs.

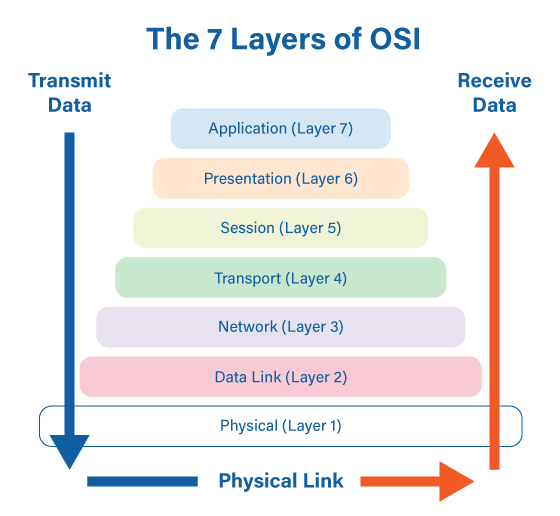

To understand the web, we have put some layers to how this awesome sequence works out. The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model acts as a reference tool for understanding communication and transfer of data between systems in a network. The OSI model comprises seven layers, each layer performing specific functions to support its neighboring layers. This layered stack basically provides flexibility, and hence these layers are quite loosely coupled.

-

Physical Layer: It consists of physical devices such as hubs, repeaters, modems, etc. which are responsible for the transfer of raw unstructured data in the form of bits. It defines the topology of devices in a network and transmits data by converting the digital bits into electrical, optical, or radio signals.

-

Data Link Layer: It comprises networking components such as NIC, Ethernet, etc. to ensure error-free transmission of data between the nodes in a network. It has two sub-layers, Medium Access Control (MAC) layer that helps in flow control and multiplexing of nodes over the network, and Logical Link Control (LLC) layer that provides flow and error control along with identification of network layer protocols.

-

Network Layer: Devices like routers work at the network layer to assign the destination address in the packet headers. The routers are responsible for finding the optimal path from the available multiple paths to send the data to the desired destination.

-

Transport Layer: This layer consists of protocols like Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP) that help in end-to-end delivery of data in the form of small units called segments. It is responsible for the sequencing and reassembling of segmented data along with error control.

-

Session Layer: Implementations of session layer include Zone Information Protocol (ZIP) and Session Control Protocol (SCP) that make use of remote procedure calls (RPC). Session layer is responsible for the establishment, maintenance, authentication and security between end user application processes.

-

Presentation Layer: Also known as syntax layer, it translates data into the form that the application accepts. It also assists in compression and encryption of the data if required by the application layer. Protocols like Secured Socket Layer (SSL) and File Transfer Protocol (FTP) are implemented at the presentation layer.

-

Application Layer: This layer is the closest to the user and hence includes applications like Telnet and Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP). Application layer identifies resource availability, communication partners and synchronizes communication. Hence it acts as a window for application services to access the network and display the information received by lower layers to the user.

Before we understand what is QUIC, we need to understand what problems it solves.

HTTP 1 → HTTP 2

If you’re using HTTP 1, your browser would be opening parallel connections to open up things at the same time. It doesn’t actually circumvent the head-of-line blocking problems, but surely makes them occur less frequently. It works well for the HTTP 1 but it certainly has its overheads, as it has to set-up as well as maintain all those numerous connections. By and large, HTTP 1 has three main issues:

-

TCP head-of-the-line blocking

-

HTTP head-of-the-line blocking

-

4-RTT connection setup

If our connection set-up is slow, and we incur packet loss, other packets can be blocked even though they might have arrived at the client, and if we have a slow first resource on HTTP, then it can also block the things lined behind it. The last two have solutions inferred, but they themselves have a lot of overhead by itself.

The TLS 1.2 had made a total of 4 round trips in order to set up secured connections. To optimize this time trade-off, the simplest thing to do was to do two things in one round trip. It was possible to implement this in some scenarios of TLS 1.2 and was the default for TLS 1.3, its successor, having a total of 3 round trips. To optimize this even closer, the TCP and TLS could work together by pulling out some strings, and this technology was called TCP Fast Open, where the user could send some extra data in the initial SYN packet. This was also beneficial as we were able to achieve twice the performance that we initially had and now what really was needed was a holy grail, to perform everything in just one single task. Along with the TLS evolution, HTTP went under transformation too. From the journey of HTTP 1.1 to HTTP 2, it solved the head-of-the-line blocking problem as it became better and smarter.

Now after these amazing transformations, all we wish was the ability of HTTP to perform multiple things at once. This certainly wasn’t feasible on HTTP 1, as it sends all the information in one big block without any demarcation to which resources the individual blocks belong to. This was achieved by multiplexing. Hence, HTTP 2 solves two problems at once - the HTTP head-of-the-line blocking problem and the overhead of the mitigation as seen above.

Yet, the TCP head-of-the-line blocking problem in regards to the loss of packet isn’t resolved. However, it was observed that HTTP 2 can be 5 times slower than HTTP 1 on a network with packet traffic. By now, you might be thinking that this can be resolved by introducing a new version as in previous use cases. Yet we know that there exists no TCP 2.0 . The reason being, that TCP is too popular and widespread to be modified. According to the definitions of the Internet, we all know that it is an interconnection of several devices. Now, these devices are running on their own implementations of TCP. This means, that if we try to change these TCP implementations, there is a high probability that we break some of these middle-box implementations, and hence if we wish to modify these, we have to wait until all these humongous implementations have added support for it before we can actually deploy it at a large scale.

On the whole, in order to solve the TCP head-of-the-line problem, we can either wait for a whole another decade so that everyone is on the same boat, or, we can make a bold choice, that TCP isn’t evolvable anymore and hence needs a replacement.

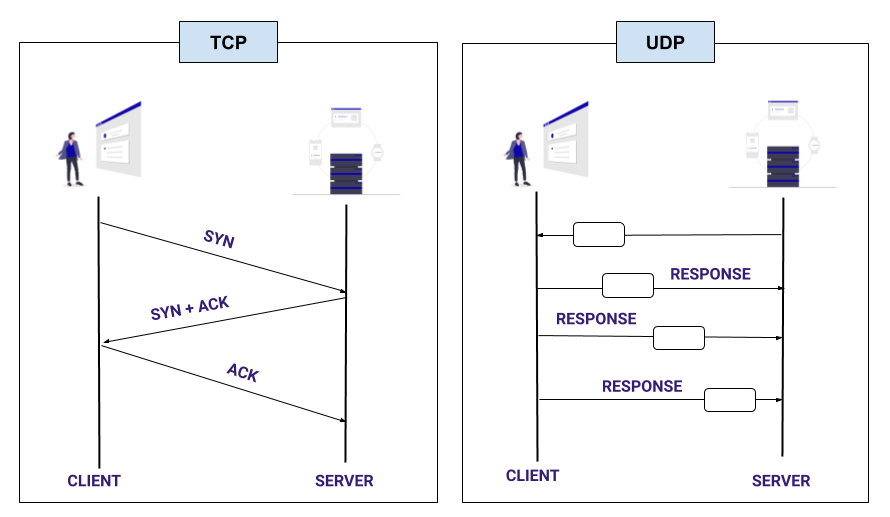

Enter UDP

UDP isn’t like the TCP at all. It is fast and doesn’t care about the packet loss.

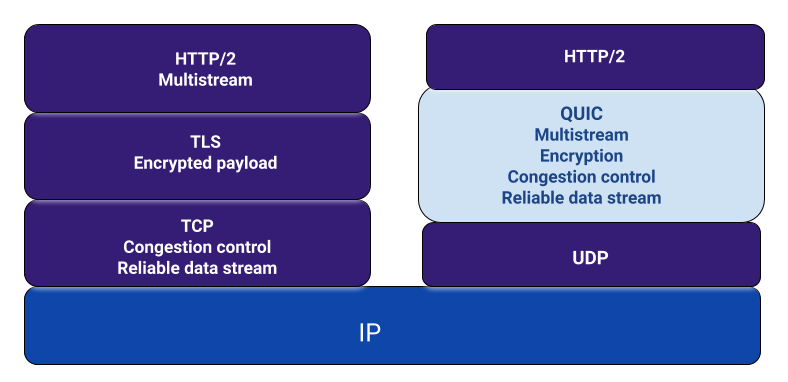

QUIC still uses TLS 1.3 . It still has that zero RTT goodness, it is built on top of UDP, and uses the HTTP 2 semantics. QUIC incorporates the multiplexing from HTTP 2 and re-implements in-order reliability on top of UDP custom top packet loss recovery logic.

This means that in QUIC if one packet is facing problems, others don’t have to be blocked due to it. Thus solving the TCP head-of-the-line problem! For solving this one problem, it is evident that a lot of effort is required at the backend. Also we know that HTTP 2 and TLS 1.3 work absolutely fine on TCP as well. So, the question arises: was it really worth the effort to solve that one TCP head-of-the-line blocking problem? The answer is NO.

Hence while developing QUIC, the developers strived to solve all the other problems as well. Consequently, QUIC is an amalgamation of everything one has known about networks over the past three decades. It’s like Christmas in a bowl!

Additional features of QUIC

Focuses on security

One of the major deviations of QUIC from the vulnerable TCP is its design goal of providing a secure-by-default transport protocol. QUIC achieves this by providing security features, like encryption and authentication, that are usually managed by higher layer protocols like TLS from the transport protocol itself.

Prevents middle box meddling through encryption

QUIC is more flexible than TCP and encrypts everything including its own metadata. Therefore the less these middle boxes get to see, the lesser they can modify. This is indeed useful for QUIC and its users, but not for the people who make these middle boxes. A lot of deliberation has been made just to come to a conclusion whether a single bit should be visible to the middle boxes or not.

Connection ID and multipath

It provides easy switching over networks. QUIC takes into account how people actually use the Internet in daily life, for say, when one is at home they are usually on WiFi, but once they step out, they switch to 4G. This closes down the TCP connection they would have established and reconnects as they now have a new IP address. However, in QUIC this is not so tiresome. QUIC instead assigns you a unique connection ID that remains the same irrespective of how many times you change your IP address. Icing on the cake, it also has the capability to use WiFi and 4G both at the same time; two networks along with extra bandwidth, which is the idea behind multipath)

Custom congestion control

It is the mechanism that prevents you from overloading the network by sending too much data. TCP has this feature as well, but it is not fairly optimal. It uses a single general-purpose algorithm and uses it for all types of connection. But it is not so generalized in case of QUIC. For instance, like a NETINFO API that lets you see what connection you’re currently using and how much bandwidth you have, it provides the perfect micro optimization for individual user and connection types for the exact moment, and even for the exact page one is trying to serve them, which makes HTTP 2 server push more practically applicable.

QUIC Performance Check

After the plethora of features that QUIC empowers us with, how much performance gain can we actually expect? And the answer is, WE DON’T KNOW! QUIC was originally developed by Google a couple of years ago. They initially deployed QUIC on their servers, and on Chrome, and is currently serving 7% of the total Internet space. QUIC hence has been battle-tested, but, only by Google. Google; the name eventually comes with trust. We like Google. If Google says something works, we say “standardize it”. This was the story of QUIC in a nutshell over past years. When we got the new IEFT version of QUIC, although it was similar to Google’s version in concept, yet it was changed to a great extent in terms of its implementation. There are several implementations of it, but none of them is even remotely ready for any type of performance testing, let alone browser integration.

Let’s talk numbers

According to Google, they found 3.6 - 8% improvement on an average over desktop and mobile devices. I’d be lying if I say I wasn’t disappointed by this. But these numbers represent an average. In 99% percentile, it shows an improvement of over 14-16%, which is indeed impactful. It might be quite evident by now that most of this improvement is due to the 0 RTT. But, one can see the 0 RTT only on servers that you’ve somehow seen/accessed before. When using mobile devices, one is likely to move around and hence Google load balances might send them to different data centers that they’ve never been before. This certainly justifies the unequal improvement rates over desktop and mobile devices.

Before you completely get all carried away in the numbers and wondering if QUIC really changed your life, let me recall for you why at the first place we switched to QUIC; and the answer is lossy networks, which is often misinterpreted as loss due to congestion. According to Google statistics, QUIC witnessed 20% less video buffering on contents in India. Another paper shows that there is a 14% of actual page load time improvement in the actual browser, which sounds pretty good. A conference paper tested QUIC with and without packet loss, and ofcourse QUIC is going to be comparatively slower with packet loss, but only 20% as compared to the 200% of HTTP/2 in most cases. Ok wow. But there are always two sides of a coin. You might be wondering why am I not citing other papers but quote the exact opposite results to the one cited till now. Well, hold your beer, here they come. There is one paper that says that QUIC is terrible for video streaming, with around 75% less Mbps than TCP for DASH streaming. Another conference paper says that if you have an inconsistent latency which causes packets to be re-ordered, QUIC is 100% than TCP. An old paper says that QUIC can have 30% slower page load time if it incurs packet loss and low bandwidth.

Conclusion

So where are we in terms of final QUIC and HTTP/3 deployment in the world? It is expected that we will see rapidly increased rollouts of QUIC and HTTP/3 by clients by the end 2020, as well as higher volume testing on pre-release channels. It will be followed by clients turning QUIC and HTTP/3 on in their stable releases. Furthermore, it is believed that QUIC and HTTP/3 will become the de-facto mainstream web protocol stack in 2021.